When Syos artist Tomoaki Baba appeared in a recent UNIQLO commercial, it was a reminder of how deeply jazz is woven into Japanese culture. Jazz is no longer a foreign influence but is part of the national soundscape, heard in cafes, clubs, arcades, and even TV spots. Baba is not an exception, but a reflection of how far jazz has come in Japan. We love back at 6 moments that cemented Jazz’s place in Japan’s musical landscape.

1. The First Arrivals: 1910s to 1920s

1. The First Arrivals: 1910s to 1920s

Jazz first arrived in Japan in the early 20th century via ocean liners carrying musicians and records between the US and Asia (including U.S. -occupied Philippines). Japanese (and Filipino) players learned from imported records and sheet music, performing ragtime and foxtrot in dance halls across Yokohama, Osaka, and Tokyo. By the 1920s, labels like Columbia and Victor were producing Japanese-language versions of American jazz hits, while local musicians formed bands and played in hotel lobbies and cabarets.

2. Tokyo March and Mass Culture

2. Tokyo March and Mass Culture

One of the first moments jazz entered Japan’s mass consciousness came in 1929, with a popular record called Tokyo March, tied to a film of the same name. According to E. Taylor Atkins, East Asian historian at Northern Illinois University and author of Blue Nippon: Authenticating Jazz in Japan, the song helped frame jazz as more than just imported entertainment. “It was associated with dance halls,” he explains, “with ‘modern girls’ and ‘modern boys,’ the Japanese version of flappers and dandies, and the urban leisure classes. Excess, and dogs and cats sleeping together, and all those sorts of portents of future calamity.”

3. Resistance and the Rise of Listening Cafés

3. Resistance and the Rise of Listening Cafés

As jazz gained popularity in Japan’s cities, it also drew pushback from conservative elites. Authorities shut down dance halls in places like Osaka, but jazz found refuge in a quieter setting: the jazz kissaten, or listening café. These cafés encouraged focused, communal listening and helped nurture a new generation of jazz fans and musicians. One of the earliest and most iconic was Chigusa, founded in 1933 in Yokohama.

When World War II broke out, Japan’s government banned jazz along with other music from enemy nations. But Chigusa’s founder, Mamoru Yoshida, refused to abandon his life’s work. With support from musicians, jazz associations, and government subsidies, the café weathered war, tragedy, and financial hardship. Remarkably, it stayed afloat for nearly a century. In 2023, Chigusa entered a new chapter, reborn as a museum dedicated to preserving its legacy and the deep roots of jazz in Japan.

4. A Postwar Revival and New Voices

4. A Postwar Revival and New Voices

After World War II, jazz returned with strength during the Allied Occupation. American GIs wanted entertainment, and Japanese musicians played in military clubs and cabarets. Swing Journal launched in 1947, becoming the country’s most important jazz publication. Jazz cafés multiplied, and live venues filled Tokyo and Osaka with local talent. Japan’s jazz scene was thriving: cozy jazz clubs and kissaten multiplied, and big band dances and concerts were popular night-life attractions. Japanese players who had grown up on wartime and prewar jazz now came into their own. Artists like Toshiko Akiyoshi and Sadao Watanabe emerged as respected voices. “When I started to play jazz in Tokyo in 1953 with Toshiko Akiyoshi’s quartet, I used to copy Charlie Parker a lot,” Watanabe said. “Then later, John Coltrane was coming up and I tried to chase him, but he was too much for me, so I gave up. So now I just play the way I feel, and try to be honest.” Akiyoshi’s early success paved the way for Japanese jazz musicians to move from imitation to individuality.

5. A New National Flavor: 1970s

5. A New National Flavor: 1970s

Musicians began blending traditional instruments and folk influences into their work, a style often referred to as “Wa-Jazz.” Flautist Minoru Muraoka introduced the shakuhachi into jazz arrangements, while Toshiko Akiyoshi incorporated taiko drums and Japanese themes into her big band compositions.

Record label Three Blind Mice, founded in 1970, played a key role by producing high-quality albums that highlighted emerging Japanese talent. Major festivals like Live Under the Sky and Mount Fuji Jazz Festival brought international and local artists together on large stages. By the end of the decade, Japanese jazz had established a confident, recognizable sound rooted in its own culture.

Hiromi Uehara performing in Warsaw, 2013

Hiromi Uehara performing in Warsaw, 2013

6. Enduring Culture and New Platforms: 1980s to Today

University big bands, supported by contests like the Yamano Big Band Jazz Contest, have produced generations of skilled players and helped sustain the talent pipeline nationwide.

New stages emerged in the 2000s, most notably the Tokyo Jazz Festival, now the country’s largest jazz event. Alongside festivals in Yokohama and Sapporo, these gatherings brought international artists to Japanese stages and introduced jazz to new audiences across the country.

Artists like Hiromi Uehara and Soil & “Pimp” Sessions (Here’s a clip of former Soil & “Pimp” Sessions member Motoharu Fukada playing the Scott Page Signature) redefined Japanese jazz on the world stage. Hiromi’s fusion-driven virtuosity and Soil’s punk-infused “death jazz” energized both domestic and global listeners, proving the genre’s continued relevance.

At street level, Japan’s jazz kissaten remain vital to the culture. With an estimated 600 still operating, these listening cafés preserve a quiet, intentional way of engaging with the music: offering rare records, high-end audio, and deep focus. They continue to shape how jazz is discovered, shared, and appreciated.

Through education, festivals, innovative artists, and everyday rituals like the jazz café, Japan has built one of the world’s most vibrant jazz ecosystems. What began as an import is now a living part of the country’s musical identity.

At Syos, our relationship with Japan runs deep. From working with talented artists like Tomoaki Baba, Lotta and Ami from the MOS band, Junnosuke Fujita, Masato Jaike or Hironori Ura, to collaborating with distributors like HOSCO for local access, Japan has become one of the most important parts of our community. Patrick Bartley, another Syos artist, has also made his mark in the Japanese music scene through the J-MUSIC Ensemble, a band dedicated to exploring the world of modern Japanese music through jazz, and garnering millions of views and hundreds of thousands of fans worldwide.

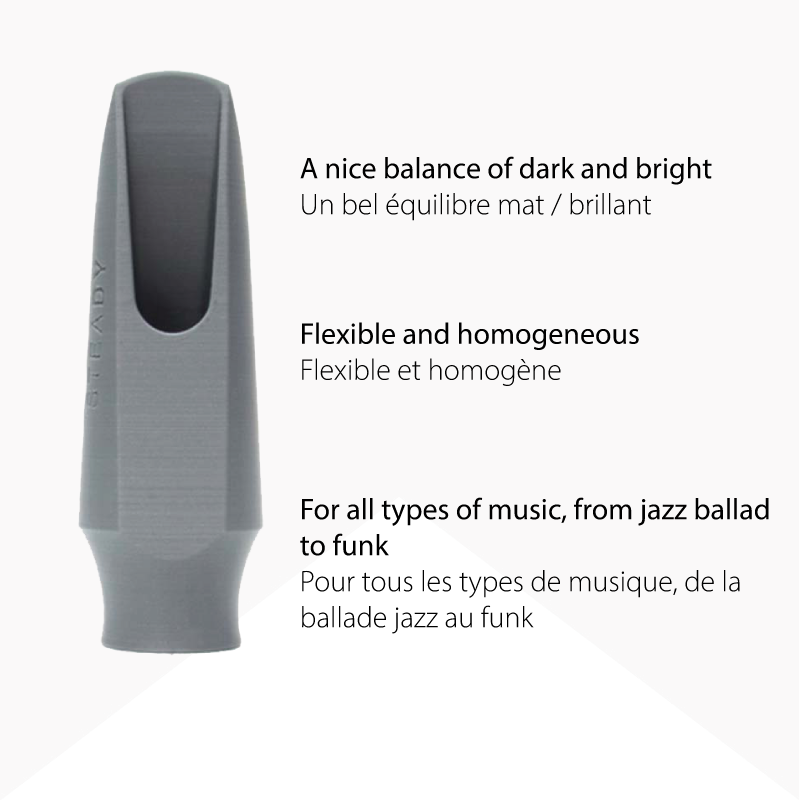

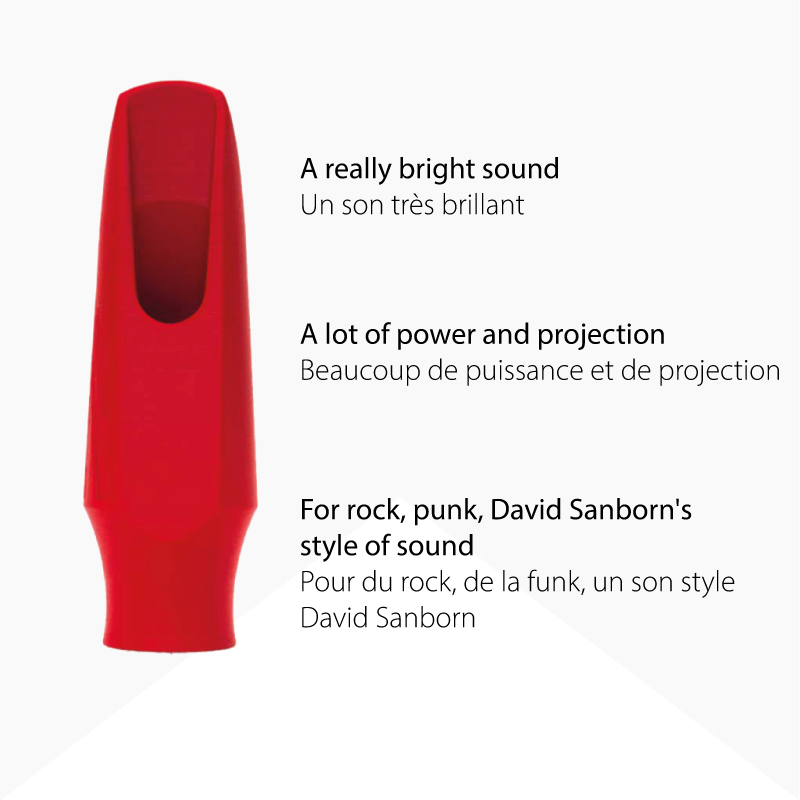

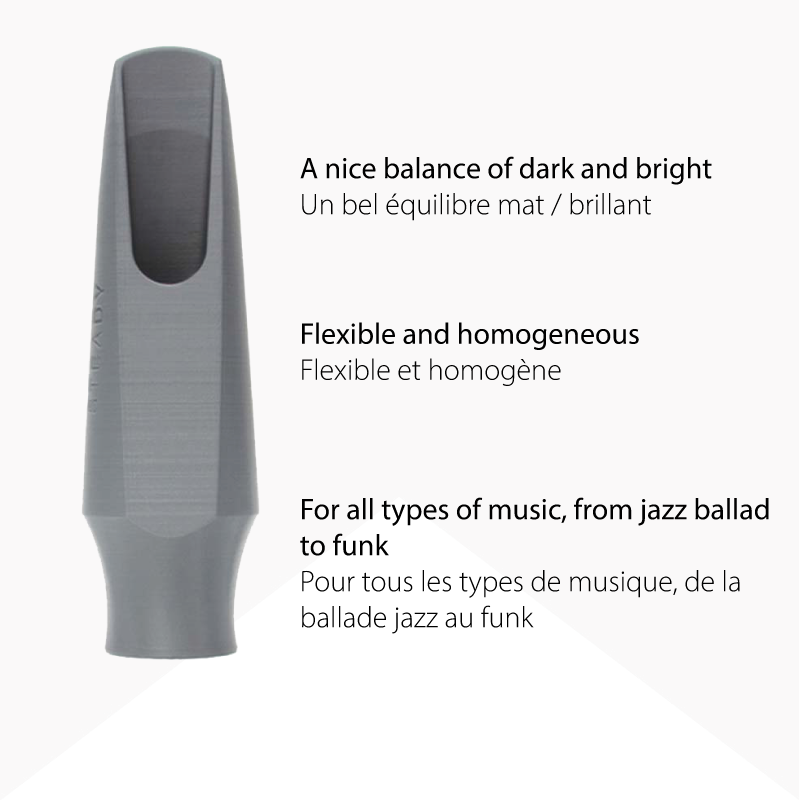

Each Syos mouthpiece is crafted to help musicians find their best sound, whether they are performing in a Tokyo club, practicing under a train bridge, or recording with a big band. Our lineup includes signature models and customizable options designed for clarity, comfort, and projection.

👉 Click here to explore Syos Saxophone mouthpieces

👉 Click here to explore Syos Clarinet mouthpieces